The shooting of maverick director Ramgopal Varma's next film ‘Bezawada Rowdilu’ is likely to begin from 21st of March. Just like the much controversial ‘Rakta Charitra,’ the film is going to be based on another controversial subject ‘rowdyism’ in the backdrop of Vijayawada. Young hero Nagachaitanya will be doing the lead role in it. Members of other cast are yet to be finalized. Ram Gopal Varma is likely to produce the film.

Popular Posts

Saturday, February 19, 2011

Pawan Kalyan, Srihari fights over Tashwa Maidan

After the debacle of Jhonny, Pawan gave up on creative works and the team got shattered.

Sridhar Reddy narrated a script titled Tashwa Maidan to Pawan Kalyan while he was in the Powerstar’s team. Pawan liked the concept but shelved it as it is similar to Lagaan. Even after coming out of Pawan’s team, Sridhar Reddy worked on the script of Tashwa Maidan and approached Srihari with it. Srihari liked it very much and started investing on Sridhar Reddy and also is planning to produce the film all by himself.

Meanwhile, Pawan Kalyan who is unaware of all this gave green to Harish Poy to make a film on Tashwa Maidan concept. Harish too worked hard on it and the subject was registered in writers association too. Sridhar Reddy was late in doing so. When Sridhar came to know about Harish Poy’s film, he met Pawan Kalyan to tell him about his hard work to the actor. But Pawan left a deaf ear to him as he felt that Sridhar Reddy is deliberately coming in between him and Tashwa Maidan.

Sridhar Reddy is hurt with the allegations that he stole the story from Pawan’s creative works and came in front of media to let the people know about what has happened. Now the issue was made public and we have to wait and see how Pawan and Srihari react to this.

paisalive.com

<a href="http://www.PaisaLive.com/register.asp?1471734-5153403"><b><font color="#FF0000" size="4">Earn upto Rs. 9,000 pm checking Emails. Join now!</font></b></a>

February 14 down the years A Valentine's Day massacre The day South Africa were bowled out for 30

|

1896

Not a day to spark celebrations in South Africa. Today they were bowled out for 30 by England in Port Elizabeth, their lowest score in Tests and the second-lowest by anyone. The deadly George Lohmann did the damage: having found his range with 7 for 38 in the first innings, he took a remarkable 8 for 7 here. Fittingly, he rounded off the match - which was over inside two days and 200 (five-ball) overs - with a hat-trick.

Not a day to spark celebrations in South Africa. Today they were bowled out for 30 by England in Port Elizabeth, their lowest score in Tests and the second-lowest by anyone. The deadly George Lohmann did the damage: having found his range with 7 for 38 in the first innings, he took a remarkable 8 for 7 here. Fittingly, he rounded off the match - which was over inside two days and 200 (five-ball) overs - with a hat-trick.

1931

A St Valentine's Day massacre. West Indies went down in two days to Australia in the fourth Test in Melbourne, bowled out for 99 and 107, with Bert Ironmonger taking 11 wickets. There was also a luscious 152 from Don Bradman to add to the 223 he made in the previous Test.

A St Valentine's Day massacre. West Indies went down in two days to Australia in the fourth Test in Melbourne, bowled out for 99 and 107, with Bert Ironmonger taking 11 wickets. There was also a luscious 152 from Don Bradman to add to the 223 he made in the previous Test.

2003

Muttiah Muralitharan may be Sri Lanka's most potent bowling weapon, but when it came to collecting one-day records, Chaminda Vaas was peerless. Already the holder of the best analysis in one-day cricket, 8 for 19 against Zimbabwe, on this day he became the first bowler to take a hat-trick with the first three balls of a match, against the hapless Bangladeshis in Pietermaritzburg. He added a fourth in the same over, en route to figures of 6 for 25, and Sri Lanka won by 10 wickets with almost 30 overs to spare.

Muttiah Muralitharan may be Sri Lanka's most potent bowling weapon, but when it came to collecting one-day records, Chaminda Vaas was peerless. Already the holder of the best analysis in one-day cricket, 8 for 19 against Zimbabwe, on this day he became the first bowler to take a hat-trick with the first three balls of a match, against the hapless Bangladeshis in Pietermaritzburg. He added a fourth in the same over, en route to figures of 6 for 25, and Sri Lanka won by 10 wickets with almost 30 overs to spare.

1968

The end of a Jamaican cracker. England were in control for most of the second Test, but after they made West Indies follow on for the second Test in a row, a century from Garry Sobers (who in the first innings went first ball to John Snow, for the second consecutive innings in which Snow had bowled to him) left England needing 159 to win on a tricky surface. Sobers and Lance Gibbs almost sent them to a sensational defeat, but they hung on at 68 for 8. All this on the sixth day of the match - an extra 75 minutes were played because of a bottle-throwing riot on the fourth day, precipitated by the dismissal of Basil Butcher.

The end of a Jamaican cracker. England were in control for most of the second Test, but after they made West Indies follow on for the second Test in a row, a century from Garry Sobers (who in the first innings went first ball to John Snow, for the second consecutive innings in which Snow had bowled to him) left England needing 159 to win on a tricky surface. Sobers and Lance Gibbs almost sent them to a sensational defeat, but they hung on at 68 for 8. All this on the sixth day of the match - an extra 75 minutes were played because of a bottle-throwing riot on the fourth day, precipitated by the dismissal of Basil Butcher.

1985

Eighteen-year-old Wasim Akram won a few battles with a 10-for in only his second Test, but New Zealand won the war with a tense two-wicket win in Dunedin today. It was even tighter than the scoreline suggests: Lance Cairns was hospitalised with a suspected fractured skull, and New Zealand were effectively nine down. Somehow Ewen Chatfield (Test average: 8) managed to stay with Jeremy Coney for 104 minutes - his longest first-class innings - while 50 runs were added. It was the difference between a 2-0 New Zealand win and a 1-1 draw.

Eighteen-year-old Wasim Akram won a few battles with a 10-for in only his second Test, but New Zealand won the war with a tense two-wicket win in Dunedin today. It was even tighter than the scoreline suggests: Lance Cairns was hospitalised with a suspected fractured skull, and New Zealand were effectively nine down. Somehow Ewen Chatfield (Test average: 8) managed to stay with Jeremy Coney for 104 minutes - his longest first-class innings - while 50 runs were added. It was the difference between a 2-0 New Zealand win and a 1-1 draw.

1968

On Valentine's Day, a charmer and a cad was born. Described by Vic Marks as "an enigma without a variation", Chris Lewis had the greatest natural talent of all England's post-Botham wannabes, and at his best he could charm the pants off any cricket lover. But too often he'd leave his admirers in the lurch with a nothing performance when it mattered: remember that ridiculous sojourn down the track to Tim May at Lord's in 1993? Or the time he shaved his head in the Caribbean and got sunstroke? Or the puncture at The Oval in 1996 that led to him being dropped for the final time? He scored a Test hundred - made in a match that was long since lost - and did help win three Tests with the ball, but Lewis could have done so much more. He drifted out of cricket at the end of 2000. In late 2008 he found guilty of smuggling cocaine into England and was sentenced to 13 years in prison.

On Valentine's Day, a charmer and a cad was born. Described by Vic Marks as "an enigma without a variation", Chris Lewis had the greatest natural talent of all England's post-Botham wannabes, and at his best he could charm the pants off any cricket lover. But too often he'd leave his admirers in the lurch with a nothing performance when it mattered: remember that ridiculous sojourn down the track to Tim May at Lord's in 1993? Or the time he shaved his head in the Caribbean and got sunstroke? Or the puncture at The Oval in 1996 that led to him being dropped for the final time? He scored a Test hundred - made in a match that was long since lost - and did help win three Tests with the ball, but Lewis could have done so much more. He drifted out of cricket at the end of 2000. In late 2008 he found guilty of smuggling cocaine into England and was sentenced to 13 years in prison.

1996

The beginning of the sixth World Cup. They say you shouldn't peak too early in a big tournament, and England followed that maxim a bit too keenly, losing an eminently winnable match against New Zealand by 11 runs. The key moment came when Graeme Hick, who played beautifully for 85, was run out after a mix-up between his runner, Mike Atherton, and Neil Fairbrother.

The beginning of the sixth World Cup. They say you shouldn't peak too early in a big tournament, and England followed that maxim a bit too keenly, losing an eminently winnable match against New Zealand by 11 runs. The key moment came when Graeme Hick, who played beautifully for 85, was run out after a mix-up between his runner, Mike Atherton, and Neil Fairbrother.

1982

Sri Lanka's first victory as a Test-playing nation. Okay, it came in a one-dayer and was largely a product of English incompetence, but they all count. Chasing 216 to win, England were cruising at 203 for 5 when the last five wickets went down for nine runs, four of them run-outs. Such a show of blind panic was pretty embarrassing for England, who did not lose to Sri Lanka in a one-dayer again for 11 years.

Sri Lanka's first victory as a Test-playing nation. Okay, it came in a one-dayer and was largely a product of English incompetence, but they all count. Chasing 216 to win, England were cruising at 203 for 5 when the last five wickets went down for nine runs, four of them run-outs. Such a show of blind panic was pretty embarrassing for England, who did not lose to Sri Lanka in a one-dayer again for 11 years.

1950

Twin hundreds for Australian opener Jack Moroney in Johannesburg, where six weeks earlier he had begun his Test career by being run out for 0. Curiously this was the only match of his seven-Test career that Australia didn't win. When they didn't win, he averaged 219; when they did, the figure was just 16.

Twin hundreds for Australian opener Jack Moroney in Johannesburg, where six weeks earlier he had begun his Test career by being run out for 0. Curiously this was the only match of his seven-Test career that Australia didn't win. When they didn't win, he averaged 219; when they did, the figure was just 16.

1995

A run-feast in the Shell Trophy match in Christchuch. Canterbury (496 and 476 for 2 dec) lost to Wellington (498 for 2 dec and 475 for 4) by six wickets in a match that produced an average of 108 runs per wicket. There were seven centuries - not a great surprise when you consider that the two teams contained a nap hand of international batsmen and allrounders. Messrs Hartland, Stead, Harris, Latham, Cairns, Astle, McMillan, Priest, Germon, Twose, Crowe and Larsen all played in this match; between them they accounted for five of those hundreds.

A run-feast in the Shell Trophy match in Christchuch. Canterbury (496 and 476 for 2 dec) lost to Wellington (498 for 2 dec and 475 for 4) by six wickets in a match that produced an average of 108 runs per wicket. There were seven centuries - not a great surprise when you consider that the two teams contained a nap hand of international batsmen and allrounders. Messrs Hartland, Stead, Harris, Latham, Cairns, Astle, McMillan, Priest, Germon, Twose, Crowe and Larsen all played in this match; between them they accounted for five of those hundreds.

Fifteen years after the last World Cup in Asia, the tournament returns to the region, but where previously a shared culture provided some of the bonds, now money talks

| |||

| Related Links Series/Tournaments: ICC Cricket World Cup | Wills World Cup | |||

Once upon a time there was a World Cup in the neighbourhood. Actually "once upon" was only 15 years ago, when there was a neighbourhood, of the kind that is unrecognisable today.

The World Cup turns up in the sport's most populous, tempestuous, and now richest, region, as South Asia's mild winter begins to depart. It returns to a continent that, for the most part, may look to the outsider as it did in 1996. It continues to pulse with strife and whirl around with the certainty of the unforseeable. What is actually coming back to Asia is a very different game, which will take place in an environment transformed.

Between 1996 and 2011 cricket has gone through its own climate change - one that has spread through the game, the players, their support cast, and been absorbed by its very ecosystem. A climate change is first noticed when, after a sizeable gap in time, we realise suddenly that the weather feels odd around us, that the seasons are neither when they used to be nor what they used to be. The World Cup is still a 50-overs-a-side competition, it is coloured clothes and white balls and black sightscreens, but something at an inherent level has shifted. The 2011 World Cup could be the event that demonstrates that shift.

Four countries, four stories

In the last 15 years the subcontinent's cricket has, mostly walked confidently. The Sri Lankans will always look at the 1996 Cup as the year that marked the time they could stand tall in the short game. In the next three Cups they made a semi-final and a final, a record better than any of their neighbours. Sri Lanka are also ahead of them in terms of current win-loss record and in performances at big events like the Champions Trophy and the World Cup. The country has put out two new venues for the World Cup, one of which is Pallekelle. The second, thanks to its president, intends to be a whole new port town and international charter-flight destination, built off a rural stretch of seaside, Hambantota. Sri Lanka has moved ahead from 1996.

In the last 15 years the subcontinent's cricket has, mostly walked confidently. The Sri Lankans will always look at the 1996 Cup as the year that marked the time they could stand tall in the short game. In the next three Cups they made a semi-final and a final, a record better than any of their neighbours. Sri Lanka are also ahead of them in terms of current win-loss record and in performances at big events like the Champions Trophy and the World Cup. The country has put out two new venues for the World Cup, one of which is Pallekelle. The second, thanks to its president, intends to be a whole new port town and international charter-flight destination, built off a rural stretch of seaside, Hambantota. Sri Lanka has moved ahead from 1996.

Bangladesh's entry into the World Cup was only as recently as 1999, and in their third attempt, in 2007, they beat India and South Africa. In July 2009 there was an away series win against West Indies, and in 2010 they recorded their first-ever win over England and beat New Zealand 4-0 at home. Whatever else it may turn out to be, Bangladesh's first World Cup at home will be a coming-out party of a cricketing country that now believes.

It is, of course, India that has grown the quickest from 1996. Its cricket team in this time shook off match-fixing and took giant strides. It upset the old order and entertained audiences. At another level, however, the nation that first cleared its throat and then demanded to be heard by the Anglocentric powers, has now turned into the game's loudest bully, ready to flex its muscle and flaunt its wealth. India now remodels and control cricket's economy, and in the new order it chooses to play autocrat, not leader. On the balance sheet they would call that a 15-year profit.

Of the four countries it is Pakistan that can look at the interlude between World Cups with a heart turned to stone. In this period its cricket has in turns been vandalised, scandalised and traumatised. Every misfortune that could be brought or struck upon has been. Its team has oscillated between being a wonderment and a wreck, its future requiring both plan and prayer. In 2003 they were called the Brazil of cricket, but now even the witty lines about the "volatile Asians" have dried up. Even as Pakistan's talent supply continues to surface, its fabric wears out year after year. It is why the event that ended in Lahore the last time will begin for Pakistan in Sri Lanka.

Talk about subcontinental drift.

1996: community and sharing

Anyone over the age of 20 in South Asia should remember 1996, because it was the neighbourhood's event. Called the Wills World Cup, it travelled everywhere, uncaring about the fatigue and dread of teams or TV crews. To 26 cities in three countries. Patna and Peshawar, Kandy and Kanpur.

Anyone over the age of 20 in South Asia should remember 1996, because it was the neighbourhood's event. Called the Wills World Cup, it travelled everywhere, uncaring about the fatigue and dread of teams or TV crews. To 26 cities in three countries. Patna and Peshawar, Kandy and Kanpur.

To the scorn of the sport's upper classes and the dismay of the pundits, it was the first cricket World Cup with double-digit participation: 12 nations, not eight or nine as had been let in until then.

A special hotline was set up between two offices in Karachi and Calcutta, to ensure a direct hook-up between argumentative neighbours India and Pakistan. It may have been all the better to have an argument with but actually it meant to bypass unpredictable telecommunication lines so neither middlemen nor pigeon post could become alternative means of communication.

| Between 1996 and 2011 cricket has gone through its own climate change - one that has spread through the game, the players, their support cast, and been absorbed by its very ecosystem | |||

Three weeks before the tournament began, when an LTTE attack on the Colombo business district drove away Australians and West Indians, and threatened to sink Sri Lanka's first-ever World Cup, the neighbourhood stood united. Two days before the tournament, a combined team of Indians and Pakistanis travelled to Colombo as the Asian XI. They played a solidarity match against Sri Lanka at the Premadasa Stadium. Since it was too late for a new uniform for the two-nation Asian XI (and neither would want to wear each other's colours), a simple solution was found: the players wore white. The sightscreen, painted black for the ODI against Australia that would never happen, was given a rushed early-morning whitewash. Sure, everything was patched together in a hurry - the symbolism, the teams, the game - but it was done. On a working day 10,000 turned up to watch.

Fifteen years ago the neighbourhood pulled together instinctively. Today it doesn't look the same. It certainly doesn't act the same. Linkages once made of a shared locality, a similar, sometimes shared, culture, are now made mostly by international bank transfers. Between then and now the game has been transformed technically, statistically, economically and politically. The equations between nations have also been altered, the power structures completely restructured.

Sure, the 1996 World Cup was far from innocent amateurism and pristine organisation. Its flaws went deep, well beyond its comically tacky opening ceremony, where the laser show bombed as a Hooghly breeze blew some screens off their moorings, and ushers and performers swanned around in civvies because their costumes were stuck in traffic. Deals done around the Cup led to court cases and a bitter falling out between Jagmohan Dalmiya and IS Bindra, once allies who had changed the finances of Indian cricket.

Yet to its hosts the 1996 World Cup meant something distinct. It was about community and a sharing - of history, status and a thirst for validation. At that time Asia was a cheeky arriviste in cricket, pushing at the gates. The Grace Gates, if you like, considering the ICC was still headquartered in London. Led by the Indians, Asia banded together and worked in a pack. In War Minus The Shooting, a carefully detailed and riotously vibrant account of the 1996 World Cup, Mike Marqusee draws out the region's common thread. The Cup, he writes, was "a global television spectacle, which all three nations hoped would boost their standing in the eyes of the world... especially in the eyes of financiers and investors... all three were opening their economies... building consumer sub-cultures in the midst of mass poverty... all three were racked with ethnic intolerance and in all three the question of national identity was hotly contested".

Yes, the 2011 event will be welcomed by Asia with all its enthusiasm and energy. It has a lovely logo, a goofily named mascot (Stumpy? Distant cousin of Dumpy / Grumpy?), it has a new co-host nation. Between the two events, 2011 could well boast that it is (to steal a pop album title) Bigger, Better, Faster, More.

Like with most advertising the full truth is in the small print. Marqusee's "all three" of 1996 now stand separated. In the scheme of things, the fourth host of the 2011 World Cup, Bangladesh, is now treated by its co-host and closest cricketing neighbour as a fringe player on the field and in the boardroom. The only country never to have hosted Bangladesh in a Test series is India. Other than ICC events, the last time the Indians invited them to anything was a 1998 tri-nation series. Should Bangladesh need some solidarity today, it is unlikely a joint India-Pakistani-Sri Lankan squad would be jetted off to provide solace. Even if the romantic idea arose, the teams' support staff would not stand for it, two days before the opening game. The "three hosts" of 2011 are, of course, an incomplete entity. As much as the idea might anger those slaving over the final logistics, the event is covered by a lopsided atlas, which has a missing part. Independent of the reasons that have led us down this path, cricket in the here and now, without Pakistan as one of the subcontinent's hosts is somewhat bereft.

Ehsan Mani, one of those involved in the PILCOM (Pakistan India Lanka Committee) for the 1996 World Cup, says he feels a "sadness" that Pakistan is not a part of what he calls a "festival of cricket". Mani was the ICC chief who had to calm the angry bid rivals, Australia-New Zealand, in March 2006 when the Asians were late in submitting their bid compliance documents for the 2011 Cup, asking for more time. Eventually the ICC granted the extension. It was the promise of India and Pakistan's participation in South Africa's 2007 World Twenty20 event that helped them win the 2011 bid with a 7-3 vote.

Mani says, "Asia will only remain remain strong if they stay together in the long term." In the short term, the events of Lahore on March 3, 2009 have scattered the subcontinent. "First there was the failure of the Pakistan board to stick to the protocol and then to try to blame someone else," Mani says. "We live in a dangerous world. What changed after Lahore was the public perception about cricket tours in Pakistan... " In just over a month Pakistan lost more than just the rights to stage the World Cup, it lost its home matches, its moorings. The spot-fixing controversy has only made it more of a pariah, its team now loaded with the double burden of displaying ability and proving intergrity every time it plays.

| |||

Money talks, money grows

The biggest tectonic shift in the World Cup has been to do with finances, brought by their move eastward. Asia's last two World Cups worked on contradictory cash registers. The 1996 Cup, officially titled the Wills World Cup after a cigarette brand (like its 1992 Benson & Hedges predecessor) was the last time any sponsor would earn the title rights to cricket's premier tournament. Title sponsors ITC paid approxmiately US$13m (about Rs 56 crores) and the television sponsorship went for over $10m (around Rs 45 crores). At the time those figures were the great leap forward for the finances on offer in the game - or rather, on offer when India was in the mix.

The biggest tectonic shift in the World Cup has been to do with finances, brought by their move eastward. Asia's last two World Cups worked on contradictory cash registers. The 1996 Cup, officially titled the Wills World Cup after a cigarette brand (like its 1992 Benson & Hedges predecessor) was the last time any sponsor would earn the title rights to cricket's premier tournament. Title sponsors ITC paid approxmiately US$13m (about Rs 56 crores) and the television sponsorship went for over $10m (around Rs 45 crores). At the time those figures were the great leap forward for the finances on offer in the game - or rather, on offer when India was in the mix.

Nineteen ninety-six was the last "sponsor's World Cup" - every event till then and including 1996 had offered dissimilar winner's trophies and been conducted with varying marketing plans, financial ambitions, and a share of the profits to the ICC. The 1999 event was run by the ECB and profits were shared with the ICC based on a formula worked out in what then came to be called the "Mani Paper".

At one time a host nation's four-yearly pot of gold, the event was fully owned by the ICC in 2003, even though the now well-recognised 11kg, silver-gold trophy was instituted after 1996. The Cup is now the ruling body's biggest money-spinning event. Its first "property", however, was the 1999 ICC Knock-Out, now known as the Champions Trophy.

Following the 1999 World Cup, the ICC sold a package of global rights for the World Cup and the Champions Trophy to Rupert Murdoch's News Corp-owned Global Cricket Corporation for $550m for a seven-year period until 2007. The latest bundle of rights for ICC events were won by ESPNStar Sports for $1.1b, with sponsorship earnings rising to $400m from the $50m earned by the ICC in 1996.

Every World Cup will now look pretty similar in terms of signage and merchandising, the complicated business of "ambush marketing" breathing down every host's neck. The ICC says its millions are now used to develop the game outside the 10 Test-playing nations. From under 50 in 1996, the ICC has a total of 105 member nations. Yet the ICC intends to have the 2015 World Cup feature only 10 nations. Mani is not amused: "If you don't support countries that are struggling, they will go backwards. At one time two-three countries are always struggling, financially, in terms of resources in regard to the game. You can't run a viable international world sport with only three or four countries playing it."

Like 1996, maybe 2011 will also carry with it a message about Asia as well as a message to the neighbourhood. That the after-effects of climate change are felt by everyone, even gated communities.

Brian Lara vs Sachin Tendulkar

To choose between Brian Lara and Sachin Tendulkar, rate them on the comparison parameters by entering scores (+ve or -ve) in the comparison tool. The total points are automatically shown in the top row. This should help you decide. Show scoring tool.

|

| | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Rating: 4.1/5 (132 votes) | |||||||

| Place of Birth: |

|

| |||||

| Height: |

|

| |||||

| Test Debut: |

|

| |||||

| ODI Debut: |

|

| |||||

| ODI Shirt Number: |

|

| |||||

| Domestic Team: |

|

| |||||

| Test Matches: |

|

| |||||

| Test Innings: |

|

| |||||

| Test Runs: |

|

| |||||

| Test Not Outs: |

|

| |||||

| Highest score (Tests): |

|

| |||||

| Batting Average (Tests): |

|

| |||||

| Test Centuries: |

|

| |||||

| Test 50s: |

|

| |||||

| ODI Matches: |

|

| |||||

| ODI Innings: |

|

| |||||

| ODI Runs: |

|

| |||||

| ODI Not Outs: |

|

| |||||

| Highest score (ODI): |

|

| |||||

| Batting Average (ODI): |

|

| |||||

| ODI Centuries: |

|

| |||||

| ODI 50s: |

|

| |||||

| Full Name: |

|

| |||||

| Country: |

|

| |||||

| Sport: |

|

| |||||

| Batting style: |

|

| |||||

| Strike rate in ODI: |

|

| |||||

| Bowling style: |

|

| |||||

| Role: |

|

| |||||

| Date of Birth: |

|

|

Thota Tharani to design Jagan's launchpad

HYDERABAD: Popular art director Thota Tharani has been roped in by Y S Jaganmohan Reddy to design the dais for the launch of his political party in March.

Tollywood sources said Tharani has agreed to stop all his present assignments and concentrate on the launch of the party. "This will beat Chiranjeevi's PRP launch in Tirupati in 2008, which was reported to be attended by at least 5 lakh people," claimed a loyalist.

"We are expecting more than five lakh people to attend the public meeting in Pulivendula to launch Jagan's party," said Y S Subba Reddy, who is personally supervising the arrangements.

Several farmers near YSR memorial have come forward to give land for the meeting.

Tollywood sources said Tharani has agreed to stop all his present assignments and concentrate on the launch of the party. "This will beat Chiranjeevi's PRP launch in Tirupati in 2008, which was reported to be attended by at least 5 lakh people," claimed a loyalist.

"We are expecting more than five lakh people to attend the public meeting in Pulivendula to launch Jagan's party," said Y S Subba Reddy, who is personally supervising the arrangements.

Several farmers near YSR memorial have come forward to give land for the meeting.

Sachin all-time great, says Nadkarni

KOLKATA: Former India all-rounder Bapu Nadkarni described Sachin Tendulkar as an all-time great cricketer.

"Cricketers like (Don) Bradman, (Brian) Lara are born once in a while. Tendulkar is one of them, he is an all-time legend, a gem," the 77-year-old said while attending a programme at the Thakurpukur Cancer Hospital on Saturday.

Asked how would he have bowled to Tendulkar if he was there, the former left-arm spinner known for his tidy and economical bowling, said, "You can never set a field to a batsman like him. He will dominate you no matter how you bowl or the field you set. That's the greatness in him."

A respected name in Mumbai cricket, Nadkarni also said Twenty20 cricket was affecting the game.

"We are not getting good bowlers now-a-days and T20 has to be blamed. You cannot judge a bowler's efficiency by seeing him in short spells in T20. There has to be a lot of Test cricket that will produce good bowlers," he said.

"Cricketers like (Don) Bradman, (Brian) Lara are born once in a while. Tendulkar is one of them, he is an all-time legend, a gem," the 77-year-old said while attending a programme at the Thakurpukur Cancer Hospital on Saturday.

Asked how would he have bowled to Tendulkar if he was there, the former left-arm spinner known for his tidy and economical bowling, said, "You can never set a field to a batsman like him. He will dominate you no matter how you bowl or the field you set. That's the greatness in him."

A respected name in Mumbai cricket, Nadkarni also said Twenty20 cricket was affecting the game.

"We are not getting good bowlers now-a-days and T20 has to be blamed. You cannot judge a bowler's efficiency by seeing him in short spells in T20. There has to be a lot of Test cricket that will produce good bowlers," he said.

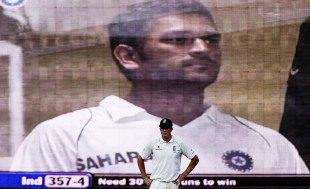

Sachin Tendulkar has World Cup date with destiny in his sights

India's greatest batsman has one last chance to win the World Cup and send his home city of Mumbai into raptures

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)